Omar Mohammed

Times of Israel, Nov. 13, 2024

“Paradoxically, this language of exclusion coexists with a widespread nostalgia for a “golden age” of interfaith harmony, a time many Arabs proudly recall as an era when Muslims, Jews, and Christians lived together in peace across the medieval Islamic world.”

Arabic is a language of extraordinary richness, embodying a vast lexicon that allows for precise expression and interpretive flexibility. This inherent complexity reflects the language’s long history, which has enabled Arabic-speaking cultures to articulate a wide range of philosophical, theological, and social ideas. Yet, this flexibility also leaves Arabic uniquely vulnerable to divergent interpretations.

For centuries, Islamic scholars and leaders have debated and reinterpreted classical texts, most notably the Qur’an, giving rise to diverse sects and schools of thought within Islam. This linguistic versatility is a double-edged sword; while it enables rich expression, it also allows for biases to seep into vernacular and everyday usage, particularly regarding Jewish people.

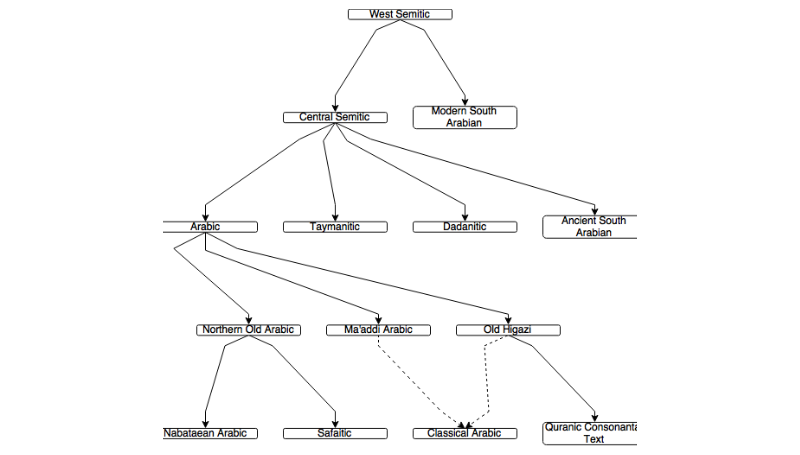

In modern Arabic-speaking societies, there is a pronounced divide between Classical Arabic, the language of official discourse, education, and religious texts, and the many spoken dialects that dominate everyday interactions. In Classical Arabic, the language of sacred texts, Jews are referenced with a linguistic neutrality that reflects early Islamic societies’ complex, sometimes contradictory, views of Jewish communities. However, in colloquial Arabic, words associated with “Jew” often carry negative connotations, implicitly tied to accusations of greed, betrayal, and malice. These associations may seem subtle but profoundly impact perceptions, perpetuating harmful stereotypes that can shape future attitudes.

… [To read the full article, click here]