Jacques Chitayat

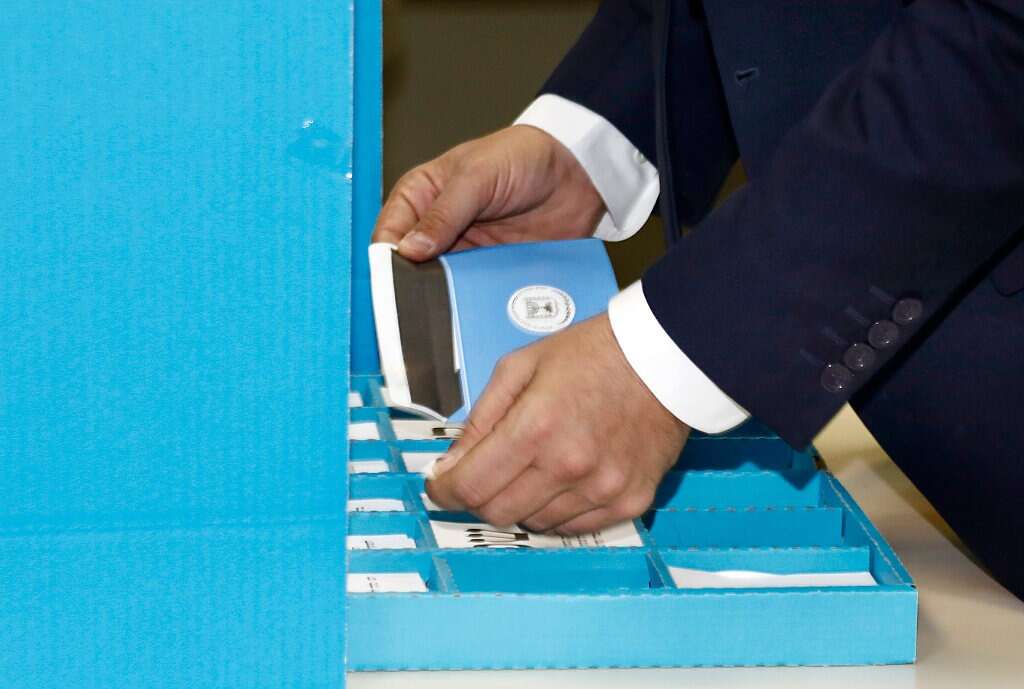

As Israel struggles with a paralyzing pandemic and a massive vaccination campaign, one can easily forget yet another issue, just as crucial, that the country faces: its upcoming election this March, their fourth in only two years, a tiring situation for most Israelis. Why does Israel have so many elections? What possible reforms can fix this vicious electoral cycle?

Israel uses a proportional voting system to elect its Knesset representatives: The number of seats each party wins is proportional to the number of votes they get within the entire country. This system is entirely different from, say, Canada’s majority system, where candidates earn a seat if they win the election in their respective riding. In Canada’s case, the party with the most seats wins the election, but not necessarily the most votes in a proportional sense. Whether a country adopts one system or another not only influences how it organizes elections: An electoral system also determines entire political landscapes and, subsequently, a country’s future.

The most significant problem of Israel’s system is that it benefits parties that gain fewer seats than those that gain considerably more, even if their support is dispersed across the country. Indeed, a vote for a small party in Israel has a more significant impact than it would in Canada since candidates do not face off in specific ridings. In the Knesset, every party can potentially gain a handful of seats suitable for democratic representation, but it makes the possibility of a party gaining a majority very difficult. In fact, in Israel’s entire history, no party has ever won a majority of the Knesset’s 120 seats.

Negotiations, compromises, and threats of breaking off from the alliance are a permanent feature of the system. Therefore, even if a party wins only a couple of seats, it has a disproportionately significant influence in the government and often assumes the role of kingmaker. Thus, any politician has much to gain in forming his own party if he can pass the threshold of 3.25% of the national vote needed. And in doing so, the number of small parties in the Knesset repeatedly multiplies, with each former cabinet minister seemingly deciding on a whim to start his or her party, reducing the chances of one party winning a majority. On March 11, 2014, the Knesset raised the threshold to 3.25% (4 seats.) Parties that fail to reach this threshold have no representation in the government.

Proportionate representation is the root of Israel’s electoral problems. Even though Netanyahu’s Likud party has won more seats with each election, he has not managed to form a stable coalition, and neither has Benny Gantz’s Blue and White party.

Israelis have always been attached to their voting system, which goes back to before the State was founded. In a 2005 research paper called Israel: The Politics of an Extreme Electoral System, scholars Michael Gallagher and Paul Mitchell explain the considerable support for proportional representation in the pre-State institutions:

“First, it was perceived as more democratic, particularly by those on the left, the side that was dominant in pre‐state politics. Second, proportionality was part of the inclusive political legacy developed in the voluntary pre‐state Jewish institutions (Sager 1985). Third, the UN partition resolution implicitly determined that the states’ future parliaments were to be elected proportionally. Finally, most of those who formulated the electoral system were representatives of small and medium‐sized parties, who preferred to stick to the formula that ensured most of them an optimal distribution of representation and power (Doron and Maor 1989).” (Gallagher & Mitchell, 2005)

The authors then review various attempts at reforming the electoral system: Electoral reform bills passed preliminary readings in the seventh Knesset (1969–73) and eighth Knesset (1973–7), while in the eleventh Knesset (1984–8), a reform bill successfully passed the first reading.

A decade later, some minor changes did take place. On May 29, 1996, the power of the Prime Minister was strengthened: To bolster his ability to form a coalition, Israelis now vote directly for Prime Minister, as well as the party of their choice. Conceivably, the one elected Prime Minister may not head the party that received the most votes, as happened in 1996 when Benjamin Netanyahu won the Prime Ministership, while Shimon Peres’ Labour Party gained the largest number of seats.

However, no initiative to reform the electoral system per se has ever reached the final legislative stages, as they explain. Most of the moderate reform initiatives demonstrated sensitivity to the smaller parties’ needs and allowed for these parties’ continued survival. So what held these reforms back? Fearing that even a moderate reform might serve as a precedent, some smaller parties put all of their political weight behind blocking any reform initiative.

“Subsequently, Israel’s ruling government always depends on unstable coalitions between big and small parties.”

As a result, Israel’s proportional voting system as conceived in 1948 has barely changed. Subsequently, the repeated elections Israelis experience show cracks in this system that gravely impacts the country’s government. Unless Israel passes a serious and impactful reform, this vicious cycle that we witness today will continue.

There are many voting systems that Israel could consider. Let’s take Canada’s electoral system as an example. As we previously mentioned, Canada uses a majority voting system, which arguably has the opposite political effect of Israel’s: Canada seldom depends on coalitions because single parties can easily win a majority of seats, often minimizing small parties’ influences. For example, in the 2019 federal election, even though the Green Party earned 1.2 million votes, it only won three seats in Parliament since their support was dispersed across the country.

In contrast, the Bloc Québécois won 1.4 million votes, and because their support was concentrated exclusively in Quebec, it won 32 seats and became Canada’s third-largest party. Adopting this system would help Israel gain some much-needed political stability and remove the smaller parties’ disproportionate influence.

However, convincing Israelis to depart from proportional representation to a majority system would be exceedingly difficult. As mentioned, Israelis are very attached to their current system. Even if the government decided to move forward with this reform, the very touchy issue of determining riding boundaries might arise, which requires many sociological, statistical, and trial-and-error experiments to get right. There is also the danger of gerrymandering when boundaries are manipulated and moved to benefit some parties or ethnicities over others unfairly.

If Israel wished to keep its proportional representation, it could also consider France’s electoral system. Like Israel, France has a vast array of political parties, both large and small, and counts its votes proportionally. Whereas Israel’s elections only have one round, France’s have two: citizens first vote for the party of their choice among all of those running, and afterward, the two parties with the most votes face off in a second round.

However, those that did not make the second round exert influence: By officially throwing their support for one party or the other, their say matters and can make a difference. In the end, this system produces stable, one-party governments. Knowing that even smaller reforms have never managed to get to the final legislative stages in Israel, passing such a reform is unlikely. And if it were to pass, it would surely come as a shock to Israelis that their ruling government only comprised a single party, which would surely spark a great deal of heated debate over democratic representation.

Whether inspired by other countries’ systems or not, Israel has many ways to escape this vicious electoral cycle, even if such prospects can seem exceedingly difficult or next to impossible. How unfortunate. With all the security, sanitary, economic, and diplomatic challenges the country faces, a stable government would be a breath of fresh air and a blessing for its future.

Jacques Chitayat is a Political Science graduate and Law student at the Université de Montréal, and a Baruch Cohen Internship Fellow at the Canadian Institute for Jewish Research.

RELATED Articles, CLICK THE IMAGES