On March 16, 2003, at the height of the Second Palestinian Intifada, Rachel Corrie, an anti-Israel activist filled to the brim with righteous fury on behalf of the Palestinians living under Israeli control, travelled with a group of comrades-in-arms to Gaza and foolishly positioned herself inside an active combat zone to bruit her political message. She died when an Israeli Defence Force armoured bulldozer ran her down. The incident caused an international furor, with dueling accounts as to fault.

Corrie’s anti-Zionist professors had encouraged her to go, having already stoked her receptive mind with images of the Palestinians as a sadly deracinated Indigenous people, their land stolen from them by rapacious imperialist Euro-colonizers.

An under-appreciated irony of the story is that Corrie’s trip was undertaken as part of a senior-year Evergreen College assignment to link her Washington state home town, Olympia, with Rafah in Gaza as a “sister city” solidarity project. It happens that her own domestic and pedagogical habitat—the territory where Olympia and Evergreen College now stand – had belonged to the Coastal Salish people since 9000 BCE, but in the 1850s was ceded to the White Man through treaties backed by false promises and lies.

Before running off to virtue-signal in Gaza, Corrie should have contemplated the hypocrisy of setting herself up on a high horse of social-justice purity regarding Middle Eastern land disputes, when its dainty hooves stood firmly planted on actually stolen land she and her anti-Zionist colleagues would never dream of actually returning to the estimated 56,000 Coastal Salish peoples living in the US and Canada.

There was huge, almost all anti-Israel press around the tragedy, but to my knowledge this aspect of the affair never came to light in the coverage. My introduction to it came from an essay, “The Convergence of the Native American and Jewish Narratives in our Times,” by Jay Corwin, a professor of Spanish and Latin American Literature of dual cultural provenance: his Indigenous mother was Tlingit of the Eagle moiety in Alaska, and his Jewish father descended from Galitzianer forebears.

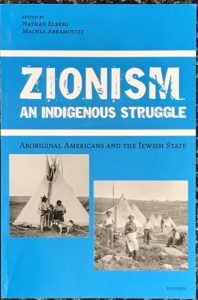

The essay is one of many in a new book, Zionism: An Indigenous Struggle: Aboriginal Americans and the Jewish State. And Corwin is one of several authors in the anthology who come to the subject of Indigeneity from the perspective of mixed Jewish-Indigenous provenance. Mining both lived experience and often unusual archival sources, these writers bring fresh, illuminating and evidence-based historical truths to a subject long freighted with a heavy code of Indigenous “correctness” they breezily ignore.

The anthology is dually edited: by anthropologist Nathan Elberg, who has had extensive experience living amongst Quebec’s James Bay area Cree Indians, as well as amongst the Eskimos of Quebec’s Hudson Bay region and the Inuit of Labrador; and by Machla Abramowitz, publications manager for the Canadian Institute for Jewish Research, a pro-Israel think tank.

The anthology’s purpose is to expose and delegitimate the relentless campaign by Palestinians and their left-wing allies in academia and the media to appropriate the suffering of North American native peoples as a propaganda tool for their anti-Israel crusade. Palestinians have co-opted the true stories of native Americans’ oppression, land theft, social marginalization, cultural and/or literal genocide to brand themselves as partners in victimization, when in historical fact no such correspondence exists.

“So if you feel that Canada is a racist endeavour (founded on stolen land, a history of genocidal policies from residential schools to the ongoing, fatal underfunding of services for Indigenous communities,) you’ll have plenty of company these days, and a healthy debate in mainstream media.

“If you argue that Israel is a racist endeavour (founded in the forced displacement of 750,000 Palestinians, still brutally enforcing the world’s longest illegal occupation, with countless discriminatory laws aimed at the Palestinian minority), the IHRA definition will be invoked to label you an antisemite.”

You see here in this overt twinning of wickedness the casual assumption that Israel’s relation to the Palestinians is the exact equivalent of the British Empire’s relationship to Canada. Given that colonialism is considered the gravest of historical crimes in the panopoly of western civilization’s evils, and native peoples its most undisputed victims, these polemicists are covertly making three assertions: that the Jews have no special claim on an ancient homeland considered sacred to them for over 3,000 years; that they are European settlers like any others who came to the New World; and that the Palestinians, not the Jews, are the Indigenous people of the land of Israel.

All are false assumptions, and the Landsberg/Lewis conflation of the two movements – imperialism and Zionism— is arguably anti-semitic itself, since it exhibits the “three D’s” that distinguish mere permissible criticism of Israel from antisemitism: demonization of Israel (using epithets like “apartheid,” “racist,” blood libels, etc), double standards in judging Jews’ ethnic national rights in a separate class from other ethnic national rights, and delegitimating Israel as a specifically Jewish state.

The essays in this anthology explain why the Landsberg/Lewis template is not only wrong but perniciously so, in some cases in granular legal detail, and in others through a literary, anthropological or historically comparative lens. The variety of approach is one of the great strengths of this little book. There is, however, one broad divide.

In one cluster, there are erudite Jewish scholars making the case for Jewish indigeneity in Israel. They write from a deep knowledge of Middle Eastern history and the torturous modern legal slog wending its way through the political jungle from the Balfour 1921 Declaration through the Paris Peace Conference, the Covenant of the League of Nations, the landmark San Remo Peace Conference, the Mandate for Palestine and so forth.

Not to disparage these essays, which speak authoritatively and eloquently to the theme, but their content, however substantive, is a reprise of material widely available in other sources. The important thing about them for my review purpose is that they establish unequivocally that by all accepted international standards, while the Palestinians may rightfully call themselves a people, the Jews are the indigenous people of the land of Israel.

The real charm and originality of this anthology lies in the vivacious and forthright voices of its Indigenous or mixed-provenance writers. They represent a circle I was hitherto unaware of, except for the remarkable Ryan Bellerose, a Métis Indian who grew up in the tiny settlement of Paddle Prairie, worlds away from Jews and Zionism, yet mysteriously acquired an affinity for Jewish peoplehood and Zionism that turned into his life’s calling. His campus activism fighting BDS brought him to my attention and then an unlikely friendship some years ago. I believed Ryan was something of a cultural unicorn, but I was happy to be proved wrong by this extraordinary collection.

Scott Benlevi, for example, is the issue of a Sephardic mother and a Native American father. In his short entry, “I Walk Two Worlds,” he tells us his Shawnee name is Walking Knife and his Israeli synagogue name – for he made Aliyah, of all the unlikely things, and is an observant Jew – is Shamir ben Togormah ben Avraham. Something wondrous here.

In “Inuit Defender of Israel,” Uqittuk Mark, an Inuk (Eskimo) Christian, has a conversation with editor Machla Abramowitz. Mark has lived his whole in Ivujivik, “an isolated wind-swept village of 380 people,” located in the Nunavut region of northern Quebec, where Mark’s people have lived for 4,000 years. He had always dreamed of visiting the Holy Land. In 2006, he did, on a Canada Awakening Ministries tour of First Nations groups. Moved by his journey into the birthplace of Judaism and Christianity, it “deepened my understanding of what needed to be done to preserve my own culture.”

To his story, editor Machla Abramowitz appends a codicil, noting that many of us have a stereotypical image of native people as “political radicals, and quick to rebuke white people.” Some native people will play that role. Mark, though, “refuses to be the aggrieved Aboriginal.” The question of “authenticity” – for both Mark as Inuk and Abramowitz as a Jew – preoccupies the interlocutors.

Editor Nathan Elberg’s essay, “Simple Truths: A Cree Indian Explains a 2,000 Year Old Rabbinic Teaching,” is a fond recollection of his relationship with Robert (Bobby) Visitor, a Cree Indian living in the small community of Wemindji, whom he met when he – Elberg – was a young anthropologist, visiting the Quebec coast of James Bay while doing research on Quebec’s great hydroelectric project on that Cree territory. Elberg recounts the chronological, superficially rather sad story of Bobby’s bare-sustenance life on the land. But the pith of his account is Bobby’s culturally-implanted indifference to wealth acquisition, speaking to a remarkable inner peace which humbles Elberg, and sparks a Jewish memory: “In Pirkei Avot, Ethics of the Fathers, we are told: Who is wealthy – he who is satisfied with his lot.'”

Ryan Bellerose’s entry in this anthology takes the form of a dialogue between himself and a fellow Indian who has drunk the Palestinians-as-Indigenous-brothers Kool-Aid. Bellerose’s friendly persuasion and well-honed arguments tease out acknowledgement that Bellerose’s logic is unassailable: it is the Jews Canada’s Indigenous peoples should be rooting for.

Dr. David A. Yeagley (1951-2014), an “enrolled Comanche Indian” and a cultural polymath, was considered the “conservative voice among American Indian intellectuals.” In his bluntly-worded essay, “There is no Palestine, There are no Palestinians,” Yeagley excoriates the American Indian Movement (AIM), formed in 1974, for its “violent and anti-American image,” because it chose to align itself with the Communist Party of America, Fidel Castro and other Marxist groups. He declares himself “appalled [that] the American Indian should be used as the mascot of the political low-life of the world.” He finds the attempt to equate the plight of the “so-called” Palestinians with American Indians “bizarre.” “Palestinian,” he writes, “does not refer to a race, language, culture, a land, or a nation. It is a political fantasy.”

Yeagley’s prose burns with the savage indignation peculiar to issue stakeholders battling kinsmen they feel betrayed by. (Nobody knows better than Jews how sharper than a serpent’s tooth it is to see fellow Jews shilling for people or groups they perceive as hostile to Jewish fortunes.) Yeagley says he was particularly offended in 2007 when he saw a group of “Palestinians” dressed up in “dime store American Indian costumes” to protest Israeli aggressions. The alleged analogy of Palestinians with American Indians is, he writes, “preposterous, stupid, and reflects the superficial emotionalism of liberals. Liberals profess great sympathy for the poor Indians…they use Indians as a symbol, a token of anti-Americanism, anti-patriotism, and anti-white racism… This places American Indians in the most pathetic, weak, and abject position possible, precluding us from any positive self-image, any development, and any real dignity in the world.”

This genre of band-aid-ripping reality check is the kind of thing that could get a white academic summarily “cancelled,” but it would take a lot more courage than most Woke academics in the progressive herd normally demonstrate to publicly smack down the strong opinions of a credentialed Indian.

In an interesting literary analysis, “Savage and Jew: A Shared Stereotype,” Howard I. Schwartz, a former professor of religious studies, explores “the overlapping stereotypes of savages and contemporary Jews in the European imagination,” finding that “[a]s a Christian anti-type, both were pictured as less than fully human, falling somewhere in the great chain of being between human and ape.”

This idea is reinforced in the above-mentioned Jay Corwin’s essay. Corwin writes that the image of the American native as the perpetual victim – “the sob story of the Americas”– is at its core a “simple religious narrative, the Christian depiction of Jesus.” Like Yeagley, Corwin’s contempt for the condescension of white liberals burns bright. He mentions the “dreadful [film] ‘Dances with Wolves’, that self-serving fantasy of the Good White Man who has come to save the people”; and suggests the film is the American equivalent to the film “Lawrence of Arabia.” Both, he claims, are “recycled Lord Jim fantasies wherein a god-like European finds himself revered by little brown people.” Both, he says, are “reinventions of the Jesus story, European style, in which the blonde haired, blue-eyed Jesus is killed by the people he tried to save.”

In 2019, responding to a report produced by an inquiry into Canada’s high numbers of missing and murdered Indigenous women, Canada’s Prime Minister Trudeau endorsed the report’s use of the word “genocide” to characterize the fate of the women, blaming disproportionate numbers of crimes against Indigenous women on “deep-rooted colonialism.” The charged word raised hackles in the Jewish community and elsewhere.

I’m not here to re-litigate the case for or against the word. I will say that anyone who thinks the residential schools were a form of genocide rather than, say, the less inflammatory but I would argue more precise “cultural suppression,” should read an essay in this anthology, “Jews, Conversos and Native Americans: The Iberian Experience,” by José Faur, a learned Jewish scholar from Buenos Aires’ Damascene Syrian community. Faur’s thesis is that “the fate of Jews, Conversos (Christians with even partial Jewish background), and Native Americans are all closely knitted” by their common victimhood of Spanish persecution.

Trigger warning: The information in this essay is riveting, but not for the faint of heart.

The brutality of the Spanish in their colonial adventures throughout the Americas cannot be over-estimated, even with reference to Hitler. Spain committed “the greatest genocide in [recorded] human history,” both absolutely and literally. In the course of about 50 years, the Iberian conquerors reduced the population of Native Americans from 80 million to 10 million. By the year 1600, the original population of Mexico was reduced from 25 million to one million.

Some of the details are too sickening to report here, but anyone versed in Holocaust sadism, especially with regard to children, knows what obscene images to conjure. All in the name of religion, there is no sugarcoating it, though some apologists have tried. Faur adduces and then demolishes their arguments via proofs delivered with the icy contempt they deserve. Why were the Spanish so unusually barbaric? “Spain is the only nation in Western Europe that did not have a Renaissance.” His provocative amplification of that statement is fascinating.

One stand-alone piece will be of special interest to Canadian readers who remember the rather disturbing “Ahenakew affair.” David Ahenakew (1933-2010) was a Canadian First Nations leader, including a term as Chief of the Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations, and another as National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations. Ahenakew harboured virulently antisemitic views of the crudest, most ignorance-based kind. He believed that Hitler “fried” German Jews because they were a threat to Germany, with the aim of taking over the world, and that they were randomly killing Arabs in the Middle East, amongst many other nasty canards.

Reportage of these publicly expressed opinions embarrassed First Nations people and shocked Canadians. Humiliatingly – only the second time in its history—Ahenakew’s Order of Canada was withdrawn, a sign of the gravity at the highest levels assigned to such hate speech. As it turned out, antisemitism amongst native Canadians was revealed, disturbingly, to be a less isolated phenomenon than supposed. A deeply-researched account of the affair and the difficulties of dealing with prejudice against Jews in general through the court system is very competently handled by Concordia University Judaic Studies professor Ira Robinson in “The David Ahenakew Affair and the Problem of Using the Canadian Justice System in the Fight Against Antisemitism.”

The most disadvantaged Indigenous peoples in Canada live far from the usual urban habitat of Jews. News about them skews to evidence of their immiseration and discontent. Indigenous-rights activists tend to present as hostile to the whole white “settler” class, which includes Jews. And to top it off, as we have seen, Indigenous ideologues are aligned with leftists and the received narrative amongst them of colonizer Zionists and Indigenous Palestinian victimhood. Most Jews in big cities therefore never get to know any Indigenous people, let alone those who are sympathetic to Israel as fellow Indigenes.

For all these reasons, I warmly commend the essays in Zionism: An Indigenous Struggle. First, for the delightful ease with which they circumvent all such contextual obstacles and speak with such buoyant admiration to the normalcy and justice of the Zionist dream. More important, because each and every one of them resists the siren call of victimhood. As Jay Corwin puts it, “[W]hile the victim is pitied, he may never be equal, and for him to ask for or demand equality means the end of victimhood.” There is nothing to be pitied about any of the Indigenous writers in this anthology. Each and every one is to be admired.

But more important, they represent an important contribution to the international debate regarding Jews’ indigeneity-based rights to sovereignty in their ancient homeland. They will hopefully serve as well to encourage friendly outreach by Jewish thinkers and leaders to potential friends and allies in this population with a view to mutually constructive collaboration.

LINK TO ORIGINAL SOURCE CLICK HERE