https://www.azquotes.com/quote/1028779

Table of Contents:

A Theological Sickness unto Death: Philip Rieff’s Prophetic Analysis of our Secular Age: Bruce Riley Ashford, Themelios, Volume 43 – Issue 1, April 2018

The West is a Third World Country: The Relevance of Philip Rieff: Carl Russell Trueman, Public Discourse, Feb. 28, 2019

The Dark Side of ‘Charisma’: Adam Wolfson, WSJ, Feb. 17, 2007

______________________________________________________Pieties of Silence

Jeremy Beer

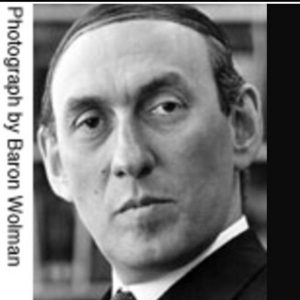

The American Conservative, Oct. 23, 2006By the time he died on July 1 at the age of 83, Philip Rieff had, quite intentionally, slipped into obscurity. His seminal Triumph of the Therapeutic had appeared 40 years earlier, the epistolary Fellow Teachers in 1973. Little had been heard from him since. Rieff published just seven articles and reviews in the entirety of the 1980s, and, until the first volume of his three-volume magnum opus was released just a few months before his death, no additional books (if one excepts the fine collection of essays, The Feeling Intellect, edited by his former student Jonathan Imber, which came out in 1990). A famously prickly man, he spent his last years in his Philadelphia townhouse, venturing out rarely, seeing few visitors, fiddling with his unfinished manuscripts. He was one of those whose obituary prompts one to exclaim: was he still alive?Yes, he was. And his withdrawal from public life was pregnant with meaning. Rieff could easily have spent his last three decades collecting the usual emoluments and honors of academia, cultivating a school of disciples, perhaps retiring into a position as a well-heeled senior fellow at a prominent think tank. But dropping out was Rieff’s counter-countercultural strategy. Whatever else its motivations, it was a singularly honest decision. In Fellow Teachers, he noted that Kierkegaard knew that “the one thing” that “would be unambiguously superior to any and all published workings-through” was “a piety of silences.” Not wanting to be “played in the ideas market,” Rieff wondered whether the “best we can do is to practice the art of silence, specially in this period of over-publication and shouting controversialists.” The rest of his life provided his answer.

It didn’t have to be that way. From his days as an undergraduate at the University of Chicago, Rieff had traced a brilliant path of academic stardom. After returning to campus from the Army Air Force, for which he had volunteered in 1943, he was offered a position on the faculty by his tutor, sociologist Edward Shils—even though Rieff had not yet even completed his bachelor’s degree. He took care of that in short order and completed his master’s degree the following year. Now a faculty instructor, he began work on his dissertation, which was to center on the reception of Freud’s ideas in America.

In 1954, Rieff completed his dissertation, which a postdoctoral grant allowed him to restructure into his first book, Freud: The Mind of the Moralist, in 1959. By that time, Rieff had scarcely had time to catch his breath; the previous nine years had been a romantic and professional whirlwind. He had become embroiled in a semi-scandalous courtship with a student, Susan Sontag, in 1950, when the 17-year-old sophomore sat in on one of his courses. Actually, the courtship was hardly long enough to be scandalous: all of ten days passed before the two were married. Nine years later, they were divorced, with Sontag taking their son David with her to New York. In the meantime, for Rieff there had been an assistant professorship at Brandeis, a visiting professorship at Harvard, a Fulbright professorship at the University of Munich, and an associate professorship at Berkeley.

The whirl calmed in 1961, when Rieff joined the faculty at the University of Pennsylvania as a full professor. But his meteoric academic rise continued. Just two years after arriving at Penn, Rieff was given a special chair as University Professor. And in 1967, he was installed as the Benjamin Franklin Professor of Sociology. At the age of 44, he was a celebrated full professor at an Ivy League university. In terms of his career, all was well and only promised to get better. … [To read the full article, click the following LINK – Ed.]

______________________________________________________

A Theological Sickness unto Death: Philip Rieff’s Prophetic Analysis of our Secular Age

Bruce Riley Ashford

Themelios, Volume 43 – Issue 1, April 2018

The great American sociologist Philip Rieff (1922–2006) stands as one of the 20th century’s keenest intellectuals and cultural commentators. Rieff did sociology on a grand scale—sociology as prophecy—diagnosing the ills of Western society and offering a prognosis and prescription for the future. Although he was not a Christian, his work remains a great gift—even if a complicated and challenging one—to Christians living in a secular age.

In his work, the Western church will find a perceptive diagnosis of Western society and culture and an illumining, though insufficient, prognosis and prescription.

1. A Therapeutic Revolution

Rieff began his academic career in the 1950s and 60s by focusing on the work of Sigmund Freud.1 In The Mind of the Moralist and The Triumph of the Therapeutic, Rieff argued that Freud’s exploration of neurosis was really an exploration of authority, as Western man was coming to view the notion of divine authority as an illusion. If God does not exist, appeals to divine authority are illegitimate. Freud recognized that as belief in God was fading, psychological neuroses were multiplying. He posited a cause-and-effect relationship between the two phenomena but, instead of healing neurosis by pointing persons back to God, Freud sought to heal it by teaching his patients to accept this loss of authority as a positive development.2

This psychotherapeutic view of modern man came to serve as a unified theory of modern society. In Rieff’s view, therapeutic ideology, rather than Communism, was the real revolution of the twentieth century. Compared to Freud, the neo-Marxists were cultural conservatives who still believed in the notion of authority and the idea of a cultural code. The proponents of Freudian therapeutics, on the other hand, would not countenance authoritative frameworks and normative moral codes. In a therapeutic culture, authority disappears. In place of theology and ethics, we are left with aesthetics and the social sciences. Thus, therapeutic culture was born. This tradeoff would turn out to be so destructive that Rieff would describe the United States and Western Europe (rather than the Soviet Union) as the epicenter of Western cultural deformation.3

2. A Sickness unto Death

Though Rieff rose to prominence as a public intellectual in the 1970s, he suddenly withdrew from the public eye for more than three decades.4 In fact, it was not until after his death in 2006 that he re-entered the public square with the publication of My Life Among the Deathworks, the first volume in a “Sacred Order/Social Order” trilogy which would bring his earlier cultural exegesis to maturation.5 … [To read the full article, click the following LINK – Ed.]

______________________________________________________

The West is a Third World Country: The Relevance of Philip Rieff

Carl Russell Trueman

Public Discourse, Feb. 28, 2019

Perhaps one of the most confusing aspects of this present age is the sheer speed with which unquestioned orthodoxies—for example, the nature of marriage, or the tight connection between biology and gender, or the vital importance of free speech to a free society—are either crumbling before our eyes or have been completely overthrown. If cultural conservatives are to respond to these changes, it is not enough to address each of them as isolated, discrete phenomena. We must first understand them as symptomatic of deeper cultural pathologies; and that requires a broader theoretical framework that sets the iconoclasm of today in the context of wider, deeper, social and cultural changes.

One thinker who can help us with this is Philip Rieff. Rieff is today justly famous for his 1966 book, The Triumph of the Therapeutic: Uses of Faith after Freud. With this remarkably prescient analysis of how personal, psychological well-being would become the primary purpose of life, Rieff spoke more truth than he could possibly have anticipated. The world in which we live today, where everything—even biological sex—is to be subordinated to how we feel inside, was barely conceivable in 1966. Today it is hard to imagine a world where the therapeutic is not normative.

Yet Rieff’s significance as a cultural critic is broader and greater than his analysis of Psychological Man, and it is here where he can help address that question of why we now have so much cultural iconoclasm of such speed and intensity. The key text is his posthumously published trilogy, Sacred Order/Social Order, where he reflects on the emerging culture of the West in a way that helps to clarify why our age subverts so much those institutions, beliefs, and practices that have traditionally defined Western civilization. The reason, Rieff argues, is a seismic change in how our society justifies its beliefs and practices, a change hundreds of years in the making whose results are now arriving thick and fast in the public square.

Sex, Religion, and Civilization

To grasp the underlying thesis of Sacred Order/Social Order, it is first helpful to understand something of Rieff’s debt to Sigmund Freud. Rieff was a scholar (and admirer) of Freud. His first major work was Freud: The Mind of the Moralist (1959), and his cultural criticism reveals debts to the psychoanalyst at several key points.

First, Rieff agrees with Freud that civilization is the result of a trade-off. For human beings, sex is the key to happiness; but if all human beings indulged their sexual instincts as they wished, there would be total chaos. Civilization therefore involves repressing and redirecting sexual urges so that people can live together in relative harmony. Nobody will enjoy perfect happiness—hence the “discontents” in the title of Freud’s famous essay, Civilization and Its Discontents—but more people will enjoy more happiness for longer than in a world of sexual anarchy. All that repressed sexual energy will go into cultural projects, such as art, music, and commerce.… [To read the full article, click the following LINK – Ed.]

______________________________________________________

The Dark Side of ‘Charisma’

Adam Wolfson

WSJ, Feb. 17, 2007

What do Angelina Jolie and Barack Obama have in common? They’ve got charisma! Ms. Jolie’s charismatic qualities are celebrated far and wide, from Time magazine (“movie-star charisma”) to the Korea Times (“sexy charisma”). Sen. Obama even rates the word in headlines, whether on WashingtonPost.com (“The Democrats’ Charisma Doctor”) or in the Chicago Tribune (“Obama Banks on Credentials, Charisma”).

“Charisma” is a word so carelessly tossed about nowadays that we hardly pause to reflect on what it means or what its common use (and abuse) may say about us. Thus the arrival of Philip Rieff’s “Charisma,” which takes this single word as a touchstone of our society and what ails it, is a welcome event.

Rieff, who died in July at age 83, was one of the country’s most distinguished sociologists. In his best-known work, “The Triumph of the Therapeutic,” published in 1965, he described how Freudian and therapeutic approaches had supplanted older understandings of society and man, much to our loss and detriment, and he questioned whether such a society could long sustain itself. His next book would have been “Charisma,” but he abandoned the project in 1973, and not until just before his death did he return to it, overseeing the final editing and authorizing the book’s publication.

It must be acknowledged that “Charisma” has a certain retro-’60s feel. Rieff denounces the “transgressive forms” of sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll, and he laments the appearance of “the organization man.” He declares that “behind the flower children of Haight-Ashbury were the cycle gangs.” But if the cultural references are somewhat dated, the central concerns of the book are as alive today as they were when Rieff began work on it some 30 years ago.

“Charisma” falls into the jeremiad category, and it bears some comparison to Allan Bloom’s best-selling “The Closing of the American Mind” (1987). Like Bloom, Rieff was a prodigiously learned scholar, and his work bristles with references to Freud, Socrates and Nietzsche, as well as German sociologist Max Weber, French anthropologist and Émile Durkheim, Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard and others. Like Bloom, Rieff puts forward a compelling critique of modernity, focusing in his case on Weber’s reworking of the religious notion of charisma into a secular, “neutral” category and thus emptying it of religious significance.

In Judaism and Christianity, “charisma” had a very specific meaning — the Greek root suggests “divine favor.” The quality might even be accompanied by miracle-making. But the key to its power was renunciation. In Judaism, as Rieff explains, charisma was tied to the notion of the Jewish covenant with God, a covenant that required its adherents to resist their more natural or animal instincts and obey certain laws and prohibitions. The same, with some modifications, could be said of “charisma” in Christian understanding. As such, charisma was not a rare possession attached to a few lucky people but a quality open to all who obeyed divine commands — in particular, the prohibitive “Thou Shalt Nots” that make genuine culture and human inwardness possible by restricting man’s self-destructive impulses. … [To read the full article, click the following LINK – Ed.]

______________________________________________________

FOR FURTHER REFERENCE:

A Tale of Two Plagiarists: Len Gutkin, The Chronicle Review, Oct. 11, 2019 — Did Susan Sontag write her then-husband Philip Rieff’s first book, Freud: The Mind of the Moralist (1959)?

The Saving Remnant: Christopher Lasch, The New Republic, Nov. 19, 1990 — “Why publish?” Philip Rieff asked himself not long ago. “With so many authors, who remains behind to read?”

Philip Rieff’s The Triumph of the Therapeutic: Uses of Faith After Freud: Darrin Moore, YouTube, Nov. 14, 2019 — This book is so important but yet so difficult that I have transcribed and read aloud its introductory chapter so that you may read along. I pepper my reading with asides, explanations, and arguments to help with comprehension.

Conversations with History: David Rieff: University of California Television (UCTV), YouTube, Aug. 15, 2008 –– UC Berkeley’s Harry Kreisler interviews author David Rieff who talks about his new book A Bed for the Night which analyzes the evolution of humanitarian work in international affairs focusing especially on its relations with the human rights movement and political leaders.

______________________________________________________

This week’s French-language briefing is titled Communique: Qui est responsable de l’indifférence des jeunes Juifs américains envers Israël: Netanyahu ou l’assimilation? (Fev 28,2020)