Table of Contents:

Misreading Kafka: Paul Reitter, Jewish Review of Books, Fall 2010

“Germany declares war on Russia—in the afternoon, swimming lessons,” Franz Kafka wrote in his diary on August 2, 1914. The line has often been cited as an expression of Kafka’s estrangement from life, of his Weltfremdheit. And why not? After all, the incongruity conveyed in the line jars us like the one we encounter at the beginning of The Metamorphosis, where Gregor Samsa wakes up as a “monstrous vermin” and wonders: How will I ever get to work on time?

But if the famous journal entry feels Kafkaesque, it hardly leaves us with an accurate sense of what Kafka thought about the war. Indeed, a former classmate of Kafka’s recalled seeing him at an early demonstration in support of the war, “looking oddly flushed” and “gesticulating wildly.” Max Brod, his closest friend and most fervent admirer, allowed that within their circle of Jewish literati, Kafka alone had believed the German and Austrian forces would necessarily prevail. So when Kafka put a chunk of his savings into war bonds, he aimed to perform his civic duty and turn a profit.

Death by data: how Kafka’s The Trial prefigured the nightmare of the modern surveillance state: Reiner Stach, New Statesman, Jan. 16, 2014

“We now live in a society in which a person can be accused of any number of crimes without knowing what exactly he has done.”

“Kafkaesque” is a word much used and little understood. It evokes highbrow, sophisticated thought but its soupçon of irony allows those who use it to avoid being exact about what it means. When the writers of Breaking Bad titled one of their episodes Kafkaesque, they were sharing a joke about the word’s nebulousness. “Sounds kind of Kafkaesque,” says a pretentious therapy group leader when Jesse Pinkman describes his working conditions. “Totally Kafkaesque,” Jesse witlessly replies.

If the word is widely misused, it is also increasingly valuable. Last year, when the attorney and author John W Whitehead wrote about the US National Security Agency scandal in an article headlined “Kafka’s America”, the reference to Kafka clearly made sense:

On Translating Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis”: Susan Bernofsky, The New Yorker, Jan. 14, 2014

“Gregor Samsa, is the quintessential Kafka anti-hero. He has worked himself to the point of utter exhaustion to pay off his parents’ debts, and his grotesque metamorphosis is the physical manifestation of his abasement.”

This essay is adapted from the afterword to the author’s new translation of “The Metamorphosis,” by Franz Kafka.

Kafka’s celebrated novella The Metamorphosis (Die Verwandlung) was written a century ago, in late 1912, during a period in which he was having difficulty making progress on his first novel. On November 17, 1912, Kafka wrote to his fiancée Felice Bauer that he was working on a story that “came to me in my misery lying in bed” and now was haunting him. He hoped to get it written down quickly—he hadn’t yet realized how long it would be—as he felt it would turn out best if he could write it in just one or two long sittings. But there were many interruptions, and he complained to Felice several times that the delays were damaging the story. Three weeks later, on December 7, it was finished, though it would be another three years before the story saw print.

The Mad Mystic of Bratslav: Allan Nadler, JewishIdeasDaily, Nov. 1, 2010

“What of the fact that both Nahman and Kafka asked their closest friends to burn their writings, which for Kamenetz not only provides a title but establishes some deep affinity between the two figures? In fact, their respective motivations were diametrically opposed.

The most bizarre pilgrimage in Jewish history now occurs each year on Rosh Hashanah in the southern Ukrainian city of Uman. There, a motley carnival of some 20,000 penitents and spiritual seekers, mostly from Israel and America, converges on the grave of Rabbi Nahman of Bratslav (1772-1811). Himself the strangest and most paradoxical leader in the history of Hasidism and one of its most original, albeit mad, geniuses, Nahman has been an object of both literary fascination and considerable scholarly research. He also shares center stage with Franz Kafka (1888-1924) in the latest volume in the Jewish Encounters series, Burnt Books by Rodger Kamenetz.

Who was he? A great-grandson of Hasidism’s founder, Israel Baal Shem Tov (the “Besht”), Nahman believed that he possessed the reincarnated and refined souls of multiple forerunners: the biblical Moses, the first-century sage Shimon bar Yohai, the great 16th-century kabbalist Isaac Luria, and, finally, the Besht himself. Referring to himself as a cosmic hiddush, something entirely new under the sun, Nahman taught that his very existence was an unprecedented and miraculous phenomenon, and boasted that the “flame of my teachings will burn until the messiah arrives.”

Lockdowns, Or Our Fantasy of Punishment: Jacques Chitayat, Isranet, Feb. 12,2021 — In his famous novel published in 1925, The Trial, Kafka tells of Joseph K., a perfectly average bank employee.

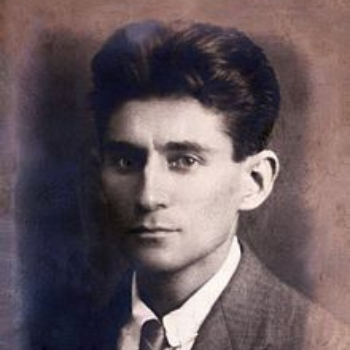

Franz Kafka: Matthue Roth, My Jewish Learning, 2021 — As his dying wish, writer Franz Kafka (1883-1924) asked that all his manuscripts be burned. If he were alive today, Kafka would be sorely disappointed.

Rare Kafka Letters in Hebrew, Finally Returned to Israel, Reveal Writer’s Deep Love for the Language: Ofer Aderet, Haaretz, Oct. 29, 2019 — At first glance, the brief letter in somewhat broken Hebrew, sent by a man to a woman nearly a century ago, seems barely worth a mention.

Benjamin Balint has written a book about the long-running “custody battle” over Franz Kafka’s legacy: Thomas Schuler, The German Times, April 2019 — This story begins and ends with betrayal – or perhaps redemption, depending on whose perspective you take.

Q and A with Rodger Kamenetz: Kafka meets Rav Nachman: Michael Orbach interviews Roger Kamenetz, The Jewish Star, Oct. 22, 2010 Issue — Rodger Kamenetz is the author of “Burnt Books: Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav and Franz Kafka.” Michael Orbach: What are the similarities between Kafka and Rav Nachman?

______________________________________________________

This week’s Communiqué Isranet is: Communiqué: Enquête de la CPI contre Israël: “De l’antisémitisme à l’état pur” (B. Netanyahou) – février 12,2021