Herman Kieval

Commentary Magazine, October 1968

“The psychoanalyst Theodor Reik contends that even Jews totally removed from any formal ties with Judaism are susceptible to Kol Nidre which, he believes, speaks to the collective Jewish unconscious of its deepest tribal memories.”

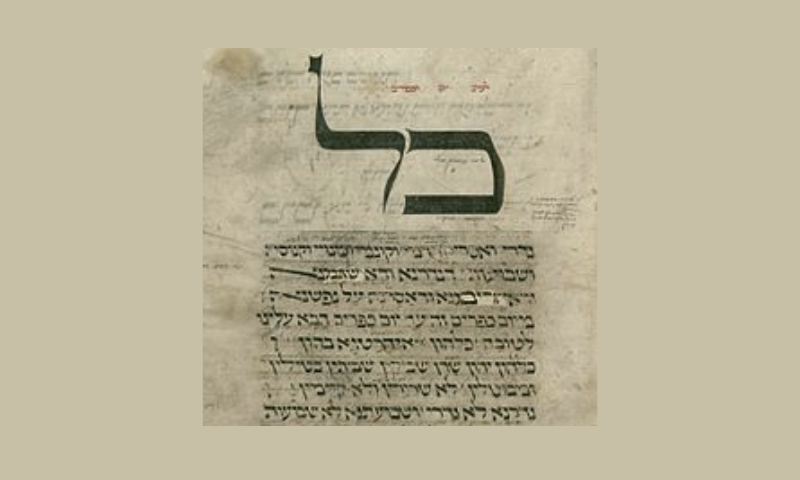

All vows, renunciations, promises, obligations, oaths, taken from this Day of Atonement till the next, may we attain it in peace, we regret them in advance. May we be absolved of them, may we be released from them, may they be null and void and of no effect. May they not be binding upon us. Such vows shall not be considered vows; such renunciations, no renunciations; and such oaths, no oaths. (Translation adapted from the High Holyday Prayer Book, edited by Rabbi Ben Zion Bokser.)

In our time, the best-known ritual of the High Holy Day services—not only among Jews but among Christians as well—is unquestionably Kol Nidre. Highlighted by its strategic location at the very inauguration of the 24-hour fast of Atonement, and chanted in a traditional melody of great spiritual force, Kol Nidre exerts an enormous impact. Yet few of the millions who experience that impact every year are aware of the paradoxical and controversial history of the Kol Nidre rite. The first of these paradoxes lies in the fact that Kol Nidre is not even a prayer, but rather a legal formula for the annulment of certain types of vows. The name of God is never mentioned. The language is a curious mixture of Aramaic—the Jewish vernacular of the Talmudic period—and Hebrew—the language of classical Jewish prayer. The style is prosaic, the wording technical. Moreover, although Kol Nidre has become virtually synonymous with the Day of Atonement, it is not, strictly speaking, part of the Yom Kippur liturgy; it is a prefatory declaration which must be recited before the sunset which ushers in the holy day.

… [To read the full article, click here]