Howard Jacobson

Sapir Journal, Vol. 8, Winter 2023

“… it is enough that the covenant enjoins a disinterested seriousness of purpose on the Jewish people and that Jewish artists and writers have found in it a spur for work of the highest order.”

The decline and fall of everything is our daily dread, we are agitated in private life and tormented by public questions,” proclaimed Saul Bellow in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech in 1976. “Give us this day our daily dread” — it would be interesting to know whether Bellow’s Stockholm audience recognized the normality, for a Jew, of Bellow’s fraught disquiet. The decline and fall of everything, including the inner man, has been a Jewish study since there was an everything to decline and fall. Hence the proliferation of Jewish prophets for whom prophecies are not so much prognostications of trouble to come as scathing commentaries on the present: diatribes and lamentations that are terrible indeed, but at last, because they describe the way we are, consoling in the way that watching a tragedy can be consoling.

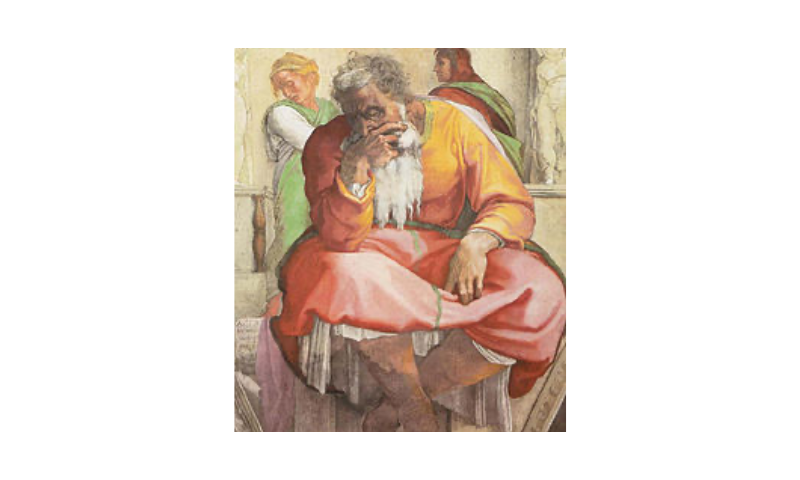

If this is to be the consequence of how we live, let us behold and own it. In making us look at the worst, the prophets performed functions we grant today to artists, writers, and even comedians who abuse us for our own good. Would it be too fantastical to think of Jeremiah and Isaiah as forerunners of Malamud and Mailer? Ezekiel as a dry run for Lenny Bruce?

I don’t mean to push personal resemblances, but the lives no less than the utterances of the great prophets are troubled in ways we have come to think of as the divine privilege of the literary. Jeremiah tells of God anointing him as a wordsmith when he was just a child, covering his mouth and telling him, “Go to all that I shall send thee, and whatsoever I command thee thou shalt speak.” … [To read the full article, click here]