Tal Fortgang

National Review, Mar. 22, 2023

“When did the Jewish tradition begin to embrace today’s notion of the “nonbinary,” and why is it news to the most devout Jews?”

Not content to enlist their twisted understandings of to fight state laws protecting unborn children, progressive activists now have taken to claiming that Judaism’s “most sacred texts reflect a multiplicity of gender,” though such a finding had been “obscured by the modern binary world until very recently.” So contends Elliot Kukla, a self-described “transgender and nonbinary” rabbi of Reform Judaism, in a shockingly shoddy New York Times guest essay.

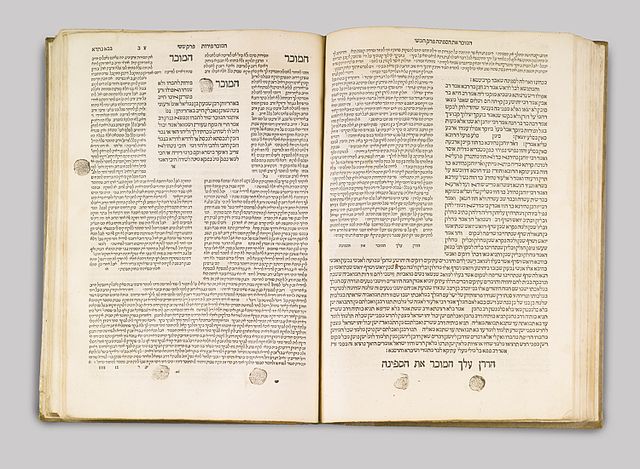

Kukla (for whom I will use masculine pronouns out of respect) reaches into the Talmud — the massive corpus of ancient Jewish law and wisdom that still forms the basis of Orthodox Jewish life today — and pulls out what he thinks is a “gotcha” concept that would show all those who devote their lives to Talmudic scholarship that they got Judaism’s teachings on gender all wrong. In doing so, he picks up a behavior popularized by Jew-haters of removing Talmudic teachings from any context to show that Judaism stands for something it very clearly does not. He also engages in a kind of appropriation that progressives would despise in other contexts: He draws on a tradition he does not consider binding (Reform Judaism rejects the applicability of Jewish law) and uses it to shout over those who do — observant Orthodox Jews, who for millennia have known well of Kukla’s “evidence” of Jewish gender ideology and have treated it in an entirely different manner.

Like an amateur archaeologist who mistakes a bottle cap for a shard of ancient pottery, Kukla has “discovered” that the Talmud does not categorize all people as typically male or female. “There are four genders beyond male or female,” he writes, “that appear in ancient Jewish holy texts hundreds of times.” These are tumtum (one who genital are obscured), androgynos (intersex), aylonit (an atypically developed female), and saris (eunuch). The Talmud, rigidly legalistic as it tends to be, is frequently interested in how to categorize these rare individuals within ancient Judaism’s highly gendered structures of Temple service, ritual purity, and much more. (By reifying categories that are relevant only in a highly binary and gender-role-driven society, Kukla thus inadvertently makes the opposite point from what he intended.)

… [To read the full article, click here]