Machla Abramovitz

Mishpacha Magazine, Feb. 9, 2022

They were the Jews of Kortelisy — close-knit, religiously committed, yet highly vulnerable.

Their village, an impoverished yet happy hamlet in the backwoods of western Ukraine, between Brest-Litovsk (Brisk) and Kowel (Kovel), was home to about 30 Jewish families among Ukrainian Orthodox Christian neighbors. But try finding Kortelisy on a map today, and you’ll search in vain, as the entire community was erased, even from the memories of the Ukrainians themselves.

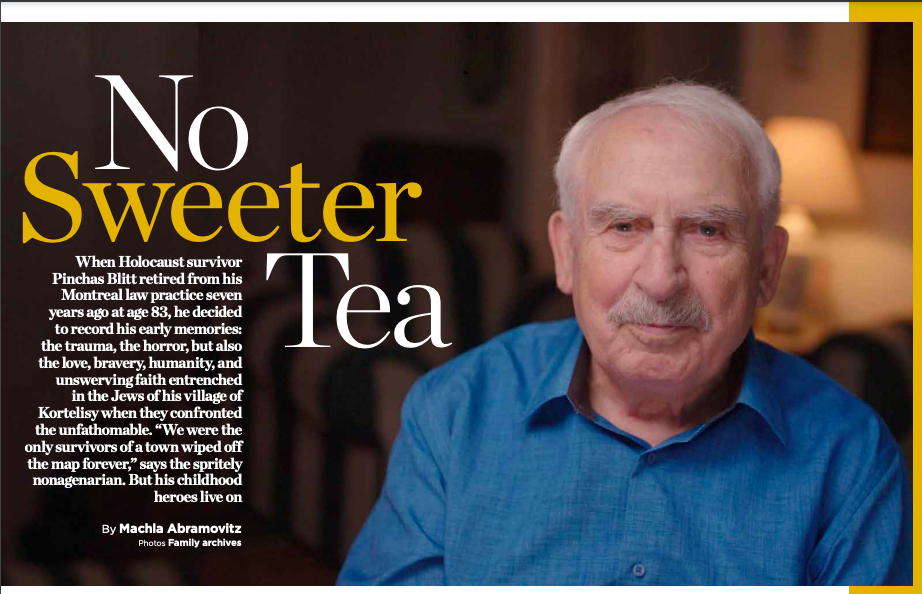

Yet Pinchas Eliyahu Blitt remembers. A master storyteller, the 90-year-old Montreal lawyer and Yiddish actor has dug into his astonishing memory, extracting the stories of his family and town-folk, vividly resurrecting the lost world of the village he deeply loved.

When Pinchas Blitt retired from his Montreal law practice just seven years ago at age 83, he sat down to write his memoirs of the Holocaust years — of the trauma, horror, but also of the bravery and salvation. That’s why the pages of his newly released A Promise of Sweet Tea, despite the dark subject matter, abound with humanity and humor, narratives that bring to life a certain kind of Jew — simple, salt-of-the-earth men and women who embodied within them the spirit of Yiddishkeit even when confronting death. The book has already been named a finalist in the Holocaust category for the National Jewish Book Awards.

“Their sense of self-worth was ingrained in them — a people to be reckoned with,” Pinchas Blitt tells me. “We knew we were the Chosen People — not chosen to destroy others, but to improve our spiritual lives. We chose the life of study and charity.”

Their commitment to “der Bashefer” was absolute. Mr. Blitt especially recalls Yisrael, “not quite a rabbi but a wise man and Talmudic scholar,” who led the community during those trying times. “He spoke of G-d as if He were his next-door neighbor to whom he talked directly and regularly. When he spoke about G-d in his sermons, you were always left with the impression that moments earlier, he had left the Almighty at the synagogue entrance or chatted with Him at the mikveh or left Him after a leisurely walk in the field.”

We’ll Dance on His Grave

We first meet Kortelisy’s Jews through the mind’s eye of five-year-old Pineleh Blitt, a happy, curious child who loves capturing dragonflies and then releasing them into the azure sky. His mother, Adele, was better educated than most village girls, having graduated from a gymnasium. At the same time, his perpetually optimistic father, Mordechai Leib, saw miracles and protective angels everywhere and never doubted that they would survive.

“We will dance on his grave, yimach shemo,” he often said, referring to Hitler. And afterward, when this cursed war would be over, he promised to take his family to Amerike, where Pineleh would drink all the sweet tea he wanted. And survive they did, hiding in marshes and forests for two years until they were liberated by the Russians in the summer of 1944. The Blitts were the sole survivors of Kortelisy.

We meet his maternal grandparents: Zeyde Berchik der kaasen, (the Angry One), although Pinchas never saw him “actually angry” and assures us that he was a good man; and the elegant and beautiful Bobbeh Frumeh, Pineleh’s beacon of salvation from the Next World. While they were living in the forest, she often appeared to him in a dream, covering him when he was cold. When he was lost, she sharply woke him from a deep sleep, forcing him to call out in the darkness so his parents could find him, covered as he was with leaves and ferns.

There was his beloved paternal Zeide Meyer, who Pineleh visited every Shabbos afternoon and often during the week. When the town fell under Soviet rule — in 1939 the region was divided up between Russia and Germany — Zeide Meyer took his life into his hands by teaching Torah in the underground cheder. Pinchas remembers how, when his town was still part of Poland, the walls of the school were decorated with Polish heroes, which all came down after the Soviet land-grab and were replaced by Lenin, Stalin, and other Soviet heroes.

“There was a time when I had a struggle between Marx and Moses within my own heart and soul,” Pinchas admits, “but I think Marx lost. Moses won. My zeide won.”

Zeide Meyer’s wife, Bobbeh Freyde, was a healer who, after having survived the initial German onslaught that decimated Kortelisy’s Jews, eventually succumbed to typhoid fever after contracting it from a friendly Christian family she was helping to heal. They took Freyde outside, and leaning against the stable walls, she died a lonely, painful death.

The Jews all resided on Kortelisy’s one main street in rough, primitive houses. Pineleh lived in a one-room wooden house with a thatched straw roof, with no running water, electricity, or indoor plumbing. The uneven floor was made of clay and streaked with crevices. In honor of Shabbos, however, they covered it with a layer of fine sand.

More than eight decades later, Pinchas smiles when recalling Shabbos in the town — how “during the week, Kortelisy Jews were beasts of burden, but on Shabbos and Yom Tov, they miraculously transformed into princes and princesses.”

Later, hiding in the outlying marshes and after that in the forest, under dramatically changed circumstances, Jewish observance continued to sustain the Blitt family: Even without a calendar, they observed Shabbos and marked all of the Yamim Tovim, celebrating with a small siddur they had with them. They even made Chanukah licht with SAP from the trees and thread from their clothing. Blitt remembers how even in the subhuman conditions of the swamps, on Shabbos his father was, in his mind’s eye, transported into a different reality. He was no longer shivering and hungry in these wet environs, but sitting in a beautiful verdant field, joyously welcoming in Shabbos. He would recite Kiddush, and the family would sing zemiros as if partaking in a feast, when their seudah consisted of some crusts of dried-out rye bread and whatever edible sustainable items they had hurriedly brought from home of scavenged.

Kortelisy may have offered little materially, but it provided everything religious Jews required: a synagogue, rabbi, shochet, cheder, and a mikveh. Only a cemetery was missing: Kortelisy Jews were buried in the cemetery of Rodin about 30 miles away, which had a more sizeable Jewish community. Five-year-old Pineleh greatly sympathized with the Christians who he watched chiseling coffins from tree trunks to bury their dead because he, as a Jew, did not expect to die. “Employing my pure and simple childish logic, I had concluded that Jews don’t die,” he remembers. “I’d never seen a Jewish man in Kortelisy chisel a burial casket, and there was no Jewish cemetery in Kortelisy.”

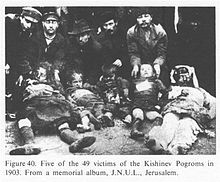

Bobbeh Frumeh did speak of the Kishinev pogrom, when Cossacks killed Jews, including children and babies; so Jews, he understood, can die, but not without outside help. But why would Cossacks kill Jews, he often asked? “Val mir zaynen Yidden — because we are Jews,” she replied.

“At the time, I thought this was a non-answer; in retrospect, I now believe it was the right and only true answer.”

Bobbe Frumeh instilled in him from a young age the need to avoid confrontations with gentiles at all costs. These warnings colored his attitude toward non-Jews. “We grew up with the feeling that because we are Jews we have to suffer, be afraid, hide. That was the mentality.”

And there was truth to that — Jew-baiting was rife in Kortelisy. Many of the Christians referred to the Jews as “crucifiers.” The Jews never fought back, but worked instead on improving their spiritual well-being. They firmly believed that the more they suffered, the closer they were to Mashiach’s arrival. When in danger, they hid behind the stables to survive. But, as Pineleh later discovered once the German soldiers arrived, “stables were not always available when looking down your executioners’ gun barrels. And stables are sometimes burned to the ground with people and animals inside.”

Still, the two communities shared a positive understanding and lived in relative harmony. The Christians provided Jews with fruits and grains, and Jews serviced them in return. No Jews were killed under the Poles nor the Soviets. It was only once the Germans arrived that being Jewish became a death sentence.

Kortelisy Jews never even considered relinquishing their Jewishness to avoid this shared fate, however. “Not like in many circles today,” Pinchas says, “where pride in being a Jew no longer exists.”

Hope and Fear

The years 1941 until his family’s liberation by the Soviets three years later, a week after he became bar mitzvah, marked a rite of passage for the young Pinchas Elye. “I never did have a real bar mitzvah,” he says, “but I had learned what it meant to be a Jew in other ways and paid a heavy price for it.”

Being Jewish, he learned, meant living on hope and fear.

For ten-year-old Pineleh, it also meant refusing to stand still and passively waiting to be shot. When still living in Kortelisy after the German invasion, he recalls the family gathering in Zeide Berchik’s home when the Ukrainian police burst inside, pointing and clicking their rifles at them. Instinctively, he jumped out the window into the night and fled. The following morning, he found his family and other Jews hovering in a neighboring stable. “We were becoming dehumanized” he says. “Parents couldn’t help their children, and children couldn’t help their parents. Everyone was on his own. We were becoming like the living dead — and that was only the beginning.”

The picture he paints of his doomed community and its faith-driven inhabitants is profoundly tragic. These industrious, clever Jews had survived under very trying conditions when their lives and well-being depended on maintaining more than cordial relations with gentiles inclined to believe the worst of them. But who could have conceived of the inhumanity unleashed by the Ukrainian police and backed by the Germans? Ironically and tragically, many of the “strong and fearless” Christians who knew how to fight back succumbed to a similar fate as the Jews.

Yet even when staring death in the face, Kortelisy’s Jews refused to relinquish their hope in humanity and the Almighty. Those like Zeide Berchik and Zeide Meyer fasted every Monday and Thursday while congregants’ prayers filled the synagogue. All the Yom Tov tefillos that year sounded like Viduy. “We prayed for atonement, for forgiveness,” Blitt remembers, “and pleaded for life — to survive the bitter humiliations and the war.”

However, the rules of survival had dramatically changed. A state of lawlessness existed, and because there were no radios or newspapers in the town, they had no idea what was happening elsewhere. “We relied on the goodwill of our Christian neighbors and the Almighty. But by the time reality set in, most of us were dead, and it was too late to do anything. In Kortelisy, it seemed like the Germans had won.

In 1942, the Germans destroyed the village and would eventually murder its entire population. However, until confronted full force with this reality, the Kortelisy Yidden still held out hope for a reprieve. But soon reality finally hit; on that first black day in the besieged village, the Germans slaughtered twenty innocent men, women, and children. Terrified, Pinchas, his immediate family, and others sought refuge in the outlying marshes, a swampland that could just as easily consume its inhabitants instead of keeping them safe. They were cold, hungry, and terrified of discovery: the Ukrainians and Nazis hunted Jews even there.

Against the Odds

On several occasions they came close to being killed. One day they heard voices approaching, and saw two people — ostensibly Ukrainian women in kerchiefs.

“One of my relatives, Hershel Blitt, who was hiding in the marshes with us, started talking to them in Ukrainian, but instead of responding, these two ‘women’ shot and killed him, together with the baby he was holding in his arms. Those “women” were really German soldiers. As they started shooting, the others in Hershel’s group began to run — some escaped, but others were killed. We were laying low nearby, squeezing ourselves into the forest floor as they ran past or were shot, as we heard the wailing of adults and children, many of them screaming out the Shema and Viduy, their screams and supplications acknowledging the Almighty as the master of the universe and of their fate silenced only by the sounds of the guns.”

After the slaughter, the Blitts were joined by a few other families, all cold and wet, terrified to move yet petrified to stay put. It was getting dark, but the Germans were still around, snuffing out the lives of the wounded and looking for more Jews to kill, including crying babies who had fallen out of their mothers’ arms.

“Finally,” Pinchas remembers, “there was not a sound, not even a whimper. Later, my father and a few others from our group went through the marshes looking for survivors, but all they found were dead bodies scattered on the ground, having fallen as they were running. There was nothing to do but bury the dead.”

After the slaughter of their group, the Blitts returned for a short period to what remained of their village. It wasn’t safe there, though, so Pinchas and his family managed to escape to nearby Ratno. His parents, together with others, sent their children to live with Ukrainian families, Christian families, where they hoped they’d be saved should Ratno be liquidated. Pinchas worked as a shepherd — in the fields during the day and in the stables at night. He was lonely and abused psychologically and physically, but his stay there saved his family. Exactly when his mother and brother visited, German and Ukrainian police liquidated Ratno’s Jews, and his father, targeted by a Ukrainian firing squad, almost didn’t make it out.

Escaping their bullets, Mordechai Leib ran in a zig-zag manner toward the beckoning Pripet River. He had recalled a farmer telling him how running in such a pattern saved his life during World War I. Here, though, the police were shooting with machine guns rather than single-bullet rifles. Still, they missed.

Mordechai Leib confronted a halachic dilemma when the water reached his neck, since he did not know how to swim. If he went forward, he would surely drown, and wasn’t suicide a sin? But if he returned to shore, the police would kill him. To die as a martyr was undoubtedly preferable to suicide but he really did not want to die — after all, his family relied on him. In the end, he decided to stay where he was, placing his faith in G-d.

“And sure enough,” says Pinchas, “der Bashefer sent Eliyahu Hanavi in the guise of a peasant accompanied by a big dog, rowing a little boat right past him.”

Whenever Pinchas’s father spoke of this miraculous deliverance from certain death, he told of seeing angels with wings surrounding him. “These angels,” he insisted, “were more powerful than hundreds of thousands of garrisons protecting a fort from the enemy.”

Pinchas says his father believed G-d’s intervention saved him, but not because he was exceptional in His eyes — it was simply G-d’s will. “G-d has His way of doing things,” his father would say, “and one should not seek explanations for the actions of the Almighty.”

After the family found Mordechai Leib alive, they decided that the best option for survival was to flee to the forest, where they remained for more than two years. Here, too, they confronted immense challenges.

“We used ferns and pine branches to build huts and for protection,” Pinchas recalls.

One night his father hiked for miles to dig up potatoes that Ukrainian farmers had buried in the sand dunes over the winter to keep them from freezing. Pinchas remembers their absolute joy when his father returned early the next morning, having trekked through deep snow carrying heavy sacks of potatoes on his thin shoulders. Those potatoes kept them alive throughout the winter. The summers were easier because they added Wild mushrooms, blueberries, and other vegetation to their menu.

Despite the cold, inadequate clothing and diet, Wild animals, and lawlessness of the Ukrainian police, the family somehow continued to survive within the forest’s protection until their liberation by the Soviet army in the summer of 1944. “We were the only Jewish family of Kortelisy to have survived,” he says.

Into Words Pinchas Blitt and his family immigrated to Canada in 1948 and settled in Montreal, where he attended college and law school. In addition to a long career as a lawyer, he was involved in the Yiddish theater community in Montreal for many years.

Pinchas finally put all those painful, traumatic memories to paper once he finally retired from his law practice in 2014 — he was a practicing lawyer for over 50 years. As he began to write, he recalled more and more details, until he had a complete manuscript which he sent to the Azrieli Foundation.

When the Azrieli Foundation read his manuscript, they immediately knew that the writer had a unique gift for storytelling.

“The memoir is an incredible story of survival and loss,” says Naomi Azrieli, chair and CEO of the Foundation. “What stands out is not only Pinchas’s resilience and inner strength but his ability to draw you into this lost community. The memoir is evocative — you can feel the community seen from the perspective of a young child. He’s also really funny — his wit and irony shine through in his writing.”

A Promise of Sweet Tea, named a finalist in the Holocaust category by the National Jewish Book Awards, is one of a hundred manuscripts published through the Foundation’s Holocaust Remembrance Memoirs Program. Rav Pinchas Hirschsprung’s A Vale of Tears is another such remarkable memoir.

The program, launched by Naomi’s father, David Joshua Azrieli, a Canadian real-estate tycoon, architect, and philanthropist, collects and publishes the memoirs of Holocaust survivors who came to Canada after the war. Like many survivors, Mr. Azrieli rarely spoke about his escape from Poland into Russia. However, when the Iron Curtain fell in 1989, he decided to retrace his journey. After Yad Vashem published the memoir, David Azrieli realized two things: How difficult it was to engage in your memories and get them on paper, and how liberating the process was as well.

“Writing memoirs is not like giving testimony in an interview where you are responding to questions; it’s you telling your story the way you want to tell it,” Naomi says.

He also realized how hard it was to publish a memoir if there is no name recognition. He suspected, correctly, that there were many valuable manuscripts out there that couldn’t find a publisher.

“Every Holocaust memoir is an act of personal liberation,” says Naomi. “For any survivor who hasn’t told their story, there’s a burden — and just being able to share it and know someone is listening is liberating. The listeners are now the witnesses. And when the last of the witnesses are gone, they know there will be more witnesses living on after them.”

As political storms brew in the distance, possibly signaling the start of a new sorry chapter in Jewish history, Pinchas Blitt has one overarching message. “I’m not a historian and I’m not a philosopher,” Pinchas says, “but I have one hope: that evil will no longer be tolerated. Because there is evil going on now in the world.”

As the world seems to be unraveling before people’s eyes, memoirs like Pinchas Blitt’s remind us of what was — and what might yet be.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 898)

Machla Abramovitz is the CIJR Publications Editor and a freelance journalist and author.

To view the article, click here