Machla Abramovitz (Publications Editor, CIJR)

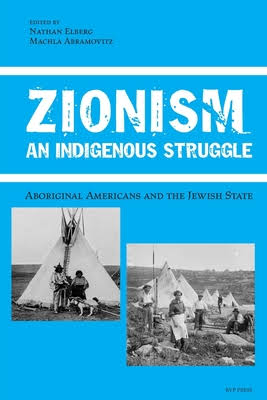

We are elated to announce the publication of our book titled Zionism: An Indigenous Struggle: Aboriginal Americans and the Jewish State. The book was published by RVP Press under the auspices of the Montreal-based Canadian Institute for Jewish Research (CIJR) and took about five years for co-editor Nathan Elberg and me to complete. Way longer than either of us anticipated. But we’re thrilled with the results and believe it was well worth the effort.

The book is an anthology of original articles – academic and personal – that focus on Native Americans and their relationship to Zionism and the Jewish state. What Native Americans think of Israel is especially relevant today considering efforts to hijack the Native American struggle for rights and recognition into the framework of Palestinian suffering. Native American writers such as Dr. David A. Yeagley and Metis native rights advocate Ryan Bellerose adamantly reject these efforts, as well as the casting of Native Americans into the role of perpetual victim. Professor Jay Corwin, whose mother was Tlingit and father Jewish, brilliantly espouses on the Christian origins behind what he calls a “pathological” and “condescending” perspective that perceives the “Good White Man” charging to the rescue of “little brown people,” whether successfully or unsuccessfully. These psychological narratives, he contends, are but recycled self-serving Lord Jim fantasies that are reinventions of the Jesus story “in which the blonde-haired, blue-eyed Jesus is killed by the people he has tried to save.”

On a more hopeful note, Uqittuk Mark, an Inuit who lives in Nunavut and who I had the privilege of interviewing, expresses his admiration for Israel and the Jewish people. Barely surviving the horrors of the Holocaust, Jews reclaimed their ancestral homeland and resuscitated their ancient language. As such, he believes, Jews have much to teach Native Americans as regards political and cultural empowerment.

The struggle for indigenous rights applies equally to Jews, especially today when their ancestral right to the Land of Israel is under attack by post-modernists and anti-nationalists who ironically have no issue with Palestinian nationalism. What, indeed, constitutes Jewish indigenous rights? Scholars such as Allen J. Hertz, Prof Sally Zerker, and Ambassador Alan Baker examine this subject from a historical/legal perspective.

Some of the most moving articles are by contributors of mixed heritage – Jewish and Native American – who expound on the challenges inherent in integrating both identities. Mara Cohen, whose ancestors stem from the Oglala Lakota People and the Levant elucidates on what it means to be an Oglala Sioux Jewish woman. Scott Benlevi (Walking Knife), the only Shawnee Jew living in Israel, proudly proclaims his love of the Land and its Creator, a consciousness he inherited from both his Native American and Jewish ancestors. For Benlevi, a religious Jew, these worlds are not disparate but complementary. “Many Native traditions mirror traditional Jewish beliefs,” he explains.

Expanding further on the Native American/Jewish/Israel relationship, Concordia University’s Prof. Ira Robinson explicates the David Ahenakew antisemitism affair that played itself out in a Canadian courtroom in 2005, and the lessons learned as regards bettering Native American-Jewish relations. Scholars Howard I. Schwartz and Jose Faur dig deeper into aboriginal history to uncover hidden Jewish connections.

As you can see, this anthology represents a broad mix of perspectives and insights into what it means – and what it doesn’t mean – to be indigenous to the land, especially in light of the darker forces out to hijack one’s identity and struggles for political purposes.

This book will be available for purchase on Amazon.ca