Barton Swain

WSJ, Nov. 24, 2023

“Is it too simplistic to say that political leaders who don’t acknowledge any authority from above are likelier to impose their will by force? If we’re nothing more than globs of cells hurtling through a chaotic universe, why not coerce people into doing what you want them to do?”

America’s political class isn’t at its best. Public life lately seems to consist mainly of self-generated disasters, easily preventable crises and media-driven hysteria. Political leaders behave like spoiled children, outrage the public to no purpose, and loudly champion ideas they know to be infeasible. Worst of all are the decisions apparently calculated to achieve the opposite of their stated goals: pandemic measures that didn’t mitigate the virus and shredded the social fabric and inflicted lasting damage on children; climate regulations that punish the poor and working class but don’t affect the climate; a military withdrawal so poorly planned that it provokes a new war; billions sent to a regime that funds genocidal attacks on an American ally; ill-advised, sometimes cockamamie prosecutions of a former president that make him more likely to regain the presidency.

Do our educated VIPs and powerbrokers have the slightest idea what they’re doing? Do they care?

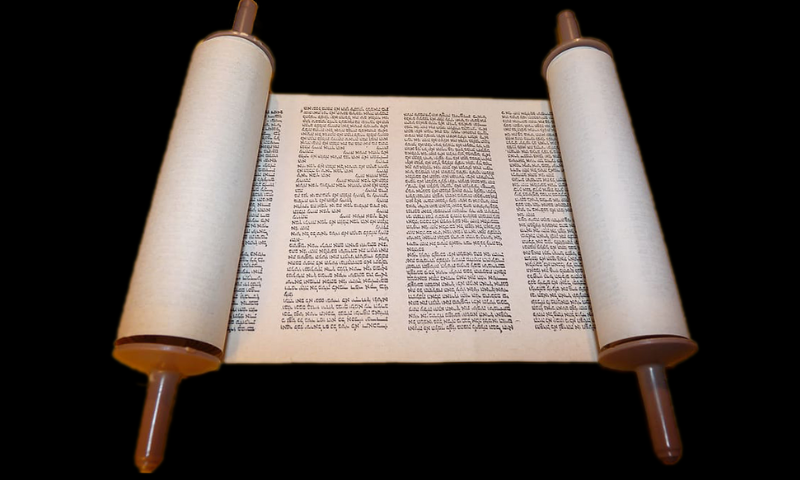

So aggressively counterproductive has the country’s political leadership become that one feels the need of a metaphysical explanation to make sense of it all. That was my thought when I read Rabbi Meir Y. Soloveichik’s “Providence and Power: Ten Portraits in Jewish Statesmanship,” published in June. The book doesn’t address today’s political controversies, but it suggests ways to think about the deeply perverse unwisdom into which so many American political leaders appear to have fallen.

Early in the book Rabbi Soloveichik refers to a 1996 essay by the Russian-born British political philosopher Isaiah Berlin (1909-97) titled “On Political Judgment.” Berlin asks: Do statesmen learn their craft from a discipline consisting of hypotheses and laws arrived at by experimentation? The answer is no, the discipline called “political science” notwithstanding. They develop a sense of practical wisdom, Berlin writes—“a capacity, in the first place, for synthesis rather than analysis, for knowledge in the sense in which traders know their animals, or parents their children, or conductors their orchestras, as opposed to that in which chemists know the contents of their test tubes, or mathematicians know the rules that their symbols obey.” … [To read the full article, click here]