by Rafael Medoff

(Dr.Rafael Medoff is an American professor of Jewish history and the founding director of The David Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies, which is based in Washington, D.C. and focuses on issues related to America’s response to the Holocaust, he is the author of more than 20 books about Jewish history and the Holocaust. His latest is America and the Holocaust: A Documentary History, published by the Jewish Publication Society & University of Nebraska Press.)

In his hit Broadway play “Leopoldstadt,” Tom Stoppard chronicles a fictional family of self-described “Austrians of Jewish descent” as they are confronted by the rise of interwar antisemitism and, eventually, the Holocaust. The chief drama critic of the New York Times has described the play as “harrowing.”

The real history of the Jews in Vienna’s Leopoldstadt district and other Jewish communities in that region is equally harrowing. The Jewish experience in the Austro-Hungarian empire through the centuries veered from relative tolerance and assimilation to blood libels and deportations—as well as a surprising connection to the U.S. government’s refusal to bomb the railways leading to Auschwitz.

Vienna’s Leopoldstadt district was given its name by antisemitic residents in gratitude to Emperor Leopold I for his mass expulsion of the Jews from that neighborhood in 1670. St. Leopold’s Church was built on the ruins of the main synagogue.

There is another city named after Leopold I, sixty-five miles to the east of Vienna. Same namesake, different backstory. In the 1660s, the emperor established a fortress there which later became the largest prison in that part of the country. The town built around it came to be known in Czech as Leopoldov, and then in German as Leopoldstadt during the Nazi occupation.

The latter Leopoldstadt is part of the Trnava region, an area rich in Czech and Slovakian Jewish history and tragedy. In 1899, the year that Tom Stoppard’s play begins, there was a major blood libel case in the Austro-Hungarian town of Polna. A young Jew named Leopold Hilsner was accused of murdering two Christian women in connection with Passover rituals.

Among Hilsner’s supporters was a little-known philosophy professor named Tomas Masaryk. He rose not merely to defend Hilsner, but, as he put it, “to defend the Christians against superstition.” Angry demonstrations by antisemitic students forced the cancelation of Masaryk’s lectures at Charles-Ferdinand University, but that did not stop him from speaking out in the later blood libel case of Menachem Mendel Beilis, in Russia.

After his election as president of Czechoslovakia in 1918, Masaryk became a strong supporter of Zionism and visited Palestine. He received honorary citizenship from the city of Tel Aviv in 1935, a forest was planted in his honor, and Czech Jewish immigrants established a kibbutz named Kfar Masaryk near Haifa in 1938.

Both Leopoldstadts—the one in Vienna, and the one in Czechoslovakia—have a place in the history of the Holocaust, although in very different ways.

The Jewish ghetto that was created in the Viennese Leopoldstadt in the 1600s was reestablished by the Nazis, in preparation for deporting its 65,000 inhabitants to Auschwitz. An estimated 97% of them were murdered.

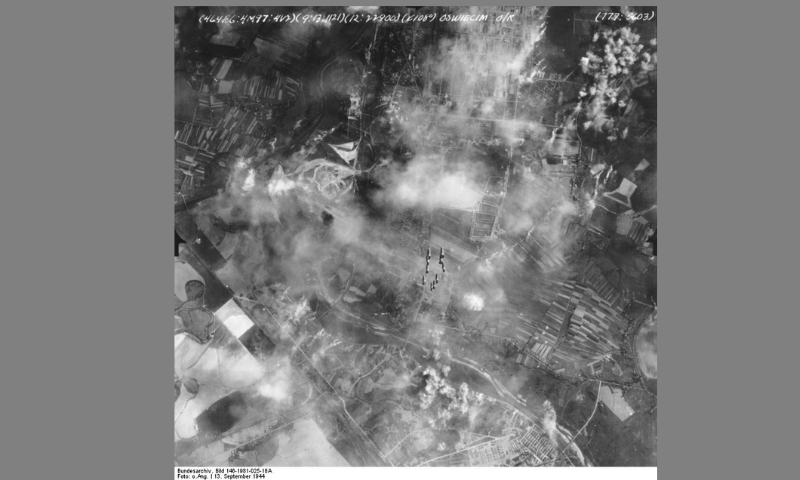

The Czechoslovakian Leopoldstadt drew attention in the spring of 1944, because it was an important hub along the railway routes used by the Germans to deport hundreds of thousands of Jews from Hungary to Auschwitz. That May, two Jewish rescue activists based in Switzerland, Yitzhak and Recha Sternbuch, presented officials at the U.S. consulate in Bern with a detailed list of the railways and bridges used for the deportations and urged them to recommend U.S. air strikes on those routes.

On June 24, Roswell McClelland, the U.S. War Refugee Board’s representative in Switzerland, sent a cable to the State Department, presenting the Sternbuchs’ request in detail. He began by explaining the brutal round-ups of Hungarian Jews and how “people were deported 60 to 70 per sealed freight wagon for a trip of two to three days without adequate water or food, probably resulting in many deaths en route.”

Regarding the potential targets, McClelland listed five specific “stretches of railroad,” one of which was “Galanta-Sered-Leopoldstadt-Novemator-Trencin.”

Significantly, McClelland’s cable pointed out that one of the routes was being used not only to deport Jews, “but also many thousand [German] troops to and from the Polish front were transported daily over this line.” That was important because it meant there was no conflict between America’s war effort and the idea of bombing the railways to interrupt the mass murder of the Jews; such an attack would serve both purposes.

The McClelland cable was one of many appeals to the Roosevelt administration, from Jewish organizations and others, pleading for bombing of the railways and bridges leading to Auschwitz or the gas chambers and crematoria in the camp. One of those advocates was Jan Masaryk, foreign minister of the Czech government-in-exile and son of the former Czech president.

“My government [has] decided to approach all Allied governments with the request to carry out the measures which you suggested,” the younger Masaryk wrote to World Jewish Congress co-chair Nahum Goldmann in July 1944, in response to Goldmann’s request for help in promoting the idea of bombing Auschwitz or the railways. But in a later follow-up letter, Masaryk reported that he ran into “considerable difficulties” when he raised the issue with Allied officials.

The main “difficulty” was that the Roosevelt administration had decided, long before the first bombing request was received, that it would not use any military resources for non-military objectives—even, apparently, when such an attack would also disrupt German troop movements. Sadly, President Roosevelt and his advisers believed the fate of Jews such as the residents of Leopoldstadt was none of America’s concern.

This article written by Dr. Rafael Medoff was originally published in the Jewish Journal.