Meir Y. Soloveitchik

Commentary Magazine, March 2020

“What is Mordecai’s true identity? What is Esther’s?”

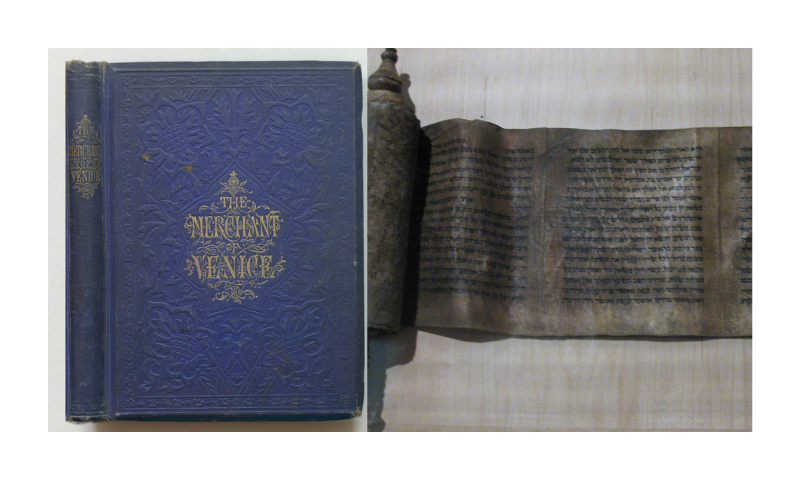

The biblical Book of Esther and Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice are opposites. One describes the Jewish triumph over anti-Semitism, the other the anti-Semite’s triumph over the Jew. Yet there are similarities between the two tales. Both emphasize inversions, a turning of the tables, through a woman’s disguising of identity. In the Bible, the king of Persia rids himself of his wife in a fit of rage, which sets the stage for a Jewish woman named Esther to become his queen. She, in turn, under the advice of her cousin Mordecai, keeps her true origin a secret: “Esther would not reveal her people or her birth.” Haman, who hates Mordecai, convinces the King to issue a decree demanding the genocide of the Jews. Esther, at an opportune moment, reveals her Jewishness to the king, and Haman is hanged.

The Merchant of Venice also centers on a heroine, Portia, who disguises herself. Shylock the Jew lends money to the Christian Antonio, who has never made his anti-Semitism a secret. Shylock therefore stresses that if the loan cannot be repaid, he will be entitled to take a pound of Antonio’s flesh. When Antonio’s ships, the source of his funds, are lost at sea, Shylock takes him to court.

Portia, in love with Antonio’s friend, dons the garb of a male lawyer. She debates with Shylock on his insistence that the letter of the law be followed. When he refuses to relent, she utilizes the very same law against him: Shylock must indeed take a pound of Antonio’s flesh, but their contract does not allow Shylock to spill a drop of Antonio’s blood. Portia has cornered Shylock: His insistence on enforcing the deal means he will have to give up his wealth and be condemned for conspiring against a Christian. The only way for him to avoid these dual fates is to convert to Christianity to save himself.

Both Merchant and Esther are thus tales of identity, and each features an astonishing line about Jewish identity itself. In Esther, the extraordinary phrase appears toward the beginning of the book: “There was a Jew, in the capital of Shushan, and his name was Mordecai.” The modern reader breezes past these words, but the ancient one would have known how shocking they are. For Mordecai was not a Jewish name, nor was Esther. Each is derived from the appellation of a Babylonian god—Esther comes from “Ishtar,” and Mordecai from “Marduk.”…SOURCE