Atar Hadari

Mosaic Magazine, Mar. 25, 2020

“Even in the throes of revolutionary uprising, these rebels are aware of the social consequences of overturning the existing order.”

On January 5, the seven-year cycle of Talmud study known as the daf yomi (“daily page”) began once more. Two months later, it still seems an apt moment to reflect on what the Talmud actually is and what sort of messages its compilers wished to convey. Part of what makes the Talmud such a unique work—and so unlike anything in the history of Western literature, theology, or legal scholarship—is that it intertwines discussions about law with stories about the people discussing it, their relationships with each other, and the human circumstances surrounding their discussions.

One of the most striking examples of this appears on pages 27 and 28 of Brakhot, the Talmud’s first tractate, which those who commit themselves to keeping up with the daf yomi cycle recently completed.

In a sense, this passage, even if it comes near the end of the third chapter, serves as an introduction to the entire Talmud: a depiction of how Jewish legal authority was established after the destruction of the Temple, and a blueprint for how Jewish law as we know it today really works. Since, like all other passages in the Talmud, this one begins in medias res, some historical background is necessary.

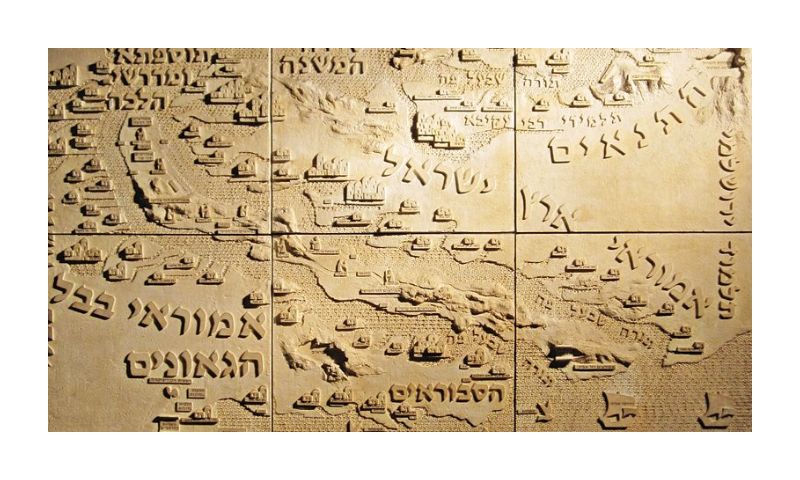

In 70 CE, Rome quashed the great uprising in Judea and destroyed Jerusalem. Rabbi Yoḥanan ben Zakkai escaped and set up a new court of Jewish learning at Yavne, a village about fifteen miles south of what’s now Tel Aviv. Ten years later, he was succeeded by Rabban Gamliel II, a rather autocratic character whose family had held the position of nasi, or president of the Sanhedrin, for generations. Yoḥanan left Yavneh to set up an academy of his own, but his students stayed behind. Among them was one Rabbi Yehoshua, the most influential scholar of his generation, who constantly challenged Rabban Gamliel.

… [To read the full article, click here]