“If a people possesses something old and profound, which can educate man and train him for his future tasks, is it truly revolutionary to despise it and become estranged from it?”

It’s become an annual modern ritual. Every summer, before Tisha B’Av, the ninth of the Hebrew month of Av, many serious Jews wonder whether to still fast on this day commemorating the First and Second Temples’ destruction—along with many other persecutions Jews endured on that day over the millennia. Especially in a united Jerusalem, with Israel about to celebrate its 75th anniversary, it seems anachronistic to recreate our grandparents’ despair yet again.

One Jerusalemite friend fasts, keens, prays—but ends the fast four hours before sundown, toasting modern Israel with biblical readings emphasizing that when redemption comes, the mourning will end. This religious dispute goes far beyond how rigorously one adheres to Jewish law. This debate, about how to remember history, and what to forget, gets to the heart of the Zionist revolution—and some democratic dilemmas today too.

In 1934, Berl Katznelson, an avowedly secular Socialist Zionist living in Tel Aviv, criticized members of his youth movement for going off to camp on Tisha B’Av. In embracing Zionism as the Jewish people’s national liberation movement, these young revolutionaries happily rejected their suffocating, depressing, religious upbringing. They ate on Yom Kippur. They had bread on Passover. And, instead of wailing on Tisha B’Av, they celebrated the Jews’ return to Zion—even before Israel’s establishment. Each assault on tradition affirmed their status as New Jews, not those pathetic, passive, pious, persecuted Yids they fled in “Galut,” exile.

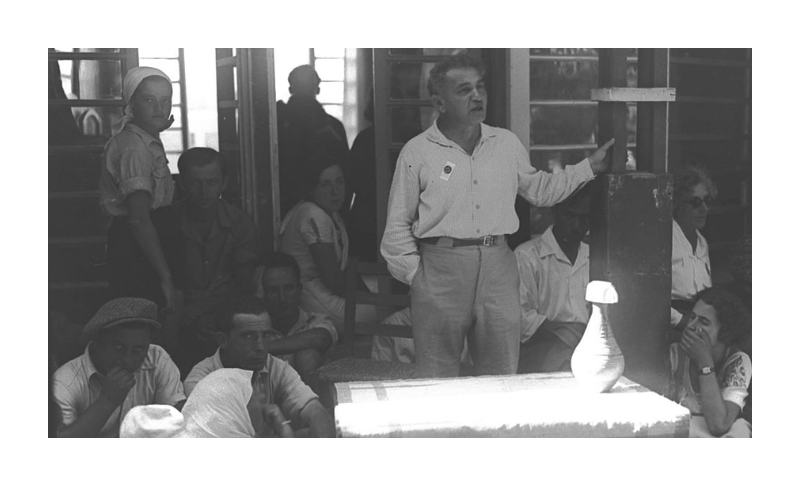

Katznelson himself enjoyed impeccable revolutionary credentials. Born in 1887 in a village called Babryusk, located in today’s Belarus, he plunged into turn-of-the-century Russia’s rousing Marxist debates. His universalist crusade for equality, however, never weakened his ties to the Jewish people or his Zionist dreams. Arriving in Palestine in 1909, he joined the trickle of “Second Aliyah” ideologues building the land—and being rebuilt by it, too.

… [To read the full article, click here]

________________________________________________________