Rabbi Eliyahu Fink

Orthodox Union, Aug. 5, 2014

“The simple version of the Roman conquest of Jerusalem in 70 C.E. is a story of superior Roman forces overwhelming a puny Jewish army. Our defeat was inevitable. But the siege and subsequent fall of Jerusalem to the Roman legions were far more dramatic and much more tragic. It’s a take of deceit, betrayal, fratricide, and ego.”

One of the biggest challenges of Tisha b’Av is finding the strength to feel pain that has had thousands of years to heal. For many people, the day ruefully memorializes our fallen temples, but unfortunately, the loss of our temple is no reason to be sad for many of our brethren. Perhaps this explains the dearth of non-Orthodox Tisha b’Av services. Why mourn for a temple if its absence is not considered a tragedy?

Even for devout Jews, who intellectually appreciate the devastation we should feel over the destruction of our temple, turning these thoughts into feelings can be extremely difficult. Knowing why a prescribed emotion is appropriate is a far cry from experiencing the sentiment on demand. “The furthest distance I’ve ever known, is the distance from my head to my heart.”

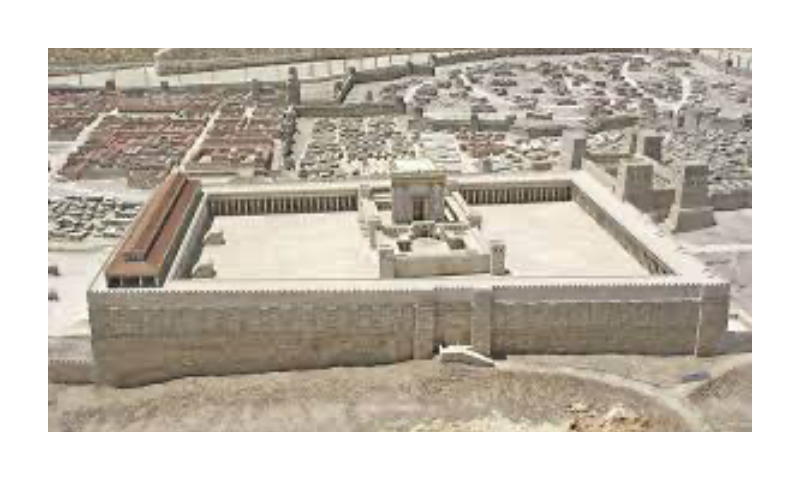

Perhaps it’s wise to aim our attention towards something that more directly touches our hearts. Tisha b’Av and the destruction of the temples in Jerusalem are not merely about architectural losses or even the loss of sacrifices and temple rituals of splendor. Indeed those are certainly lamentable, but they are so foreign to us that it can feel like trying to feel a mathematic equation. We know that the arithmetic works, but we don’t have any feelings about the numbers. Indeed, there is something far more calamitous, far more personal, far more tender, that occurred when the Second Temple was razed to the ground nearly 2,000 years ago.

Our Talmudic Sages teach that the Second Temple was destroyed due to sinat chinam — baseless hatred — between fellow Jews. Typically, this is taken to mean that the Jews of that time, much like Jews of seemingly every time, did not need an excuse for enmity towards each other. There’s nothing fancy about it. They simply hated each other and perpetuated an anti-social environment. Instead of gratuitous kindness and friendship, they exhibited gratuitous divisiveness and acrimony towards each other. For this, the Temple was destroyed. We did not deserve a Temple if we couldn’t even be friends. In a practical sense, how could we expect to work together in the Temple if we hated each other? Even in a halachic sense, how could a priest achieve atonement for another person if he didn’t even care if that other person was forgiven. Caring for one another is a prerequisite to the service in the Temple. To be sure, this is a valuable and important lesson: “A house divided against itself cannot stand” socially and religiously. … [To read the full article, clickhere]